The Super League will be remembered as a classic case study of how not to run a communications strategy

“The Super League” only existed for a handful of hours, but everybody already hates it. Heads of government, clubs, leagues, federations, football’s governing bodies have all portrayed it as their worst enemy; even the players and managers of the teams involved have taken a stand against it. So much so that, in less than 48 hours after its genesis, most of its founding clubs had already opted out. Nevertheless, its slogan was compelling:

THE BEST CLUBS.

THE BEST PLAYERS.

EVERY WEEK.

Catchy, isn’t it? So what went so wrong to make this amazing promises the worst threat that the world of football has ever received?

The most evident problem with it, and every football fan knows it, is that the very design of the Superleague is just too far from the socio-cultural view of football we have in Europe. I myself am a football fan. As such, I’ve never won anything – just like the great majority of football fans on earth – but The Super League is trying to convince me that clubs won’t lose anymore. That can’t work. A tournament where everybody wins and nobody loses, today, seems just absurd in Europe, and it honestly feels naive that the founding clubs hadn’t realised that beforehand.

However, the massive rejection of European football still seems excessive if compared to the big promise of making the extraordinary a daily business. In my opinion, a suicidal communications strategy has been critical in making the world of football reject the “The Super League” proposal.

In this article we will be reviewing this strategy. Please note that I will not make a judgement of the clubs’ reasons, yet I will just suggest the best possible communications strategy to employ in this context, as far as I’m concerned.

Was that it?

Just think about it: nowadays if I want to open a grocery store I not only can but I also must advertise it as if it were a Hollywood production. Have a modern logo, make engaging social media content. And how did The Super League announce the most revolutionising project in the history of football? With a three-page, A4, white document sent at midnight when, at best, newspapers were about to close. No media plan, no presentations, no press conferences, no interviews, no founding sponsors: just a rain of ice-cold press releases over the heads of confused fans.

The wrong message

Yes, they were in a rush. They had to anticipate the “Super” Champions League announcement. But let’s suppose timing’s not their fault and let’s see what the press release said.

In a nutshell, the message one gets by reading it is: “We, the rich football clubs, are in extreme need of money, so we make this decision that we won’t explain any further, because you, the irrelevant rest, cannot do anything about it, as we are the ones who make football the spectacle everybody likes”. Needless to say, that concept was taken as insulting by all the parties left out, and its framing didn’t convince anybody in the world of football.

By the way, have you ever seen an advertisement focused on the benefit the shop will get from selling the product, rather than the benefit the customer will get from buying it? Regardless of how the message is perceived, the decision of framing the matter like this was very bold and could not be expected to turn out to be successful.

Speaking of money. “Solidarity” was at the core of the brief communications conveyed by the founding fathers of the project. They promised that they would earn so much money that they would have given away an “uncapped” ratio of it to the rest of the system.

The big mistake here was that the only certain figure they spoke about both in the statement and the very few other communications they gave was the €3.5 billion check clubs would get from JP Morgan. On the other hand, the founders weren’t able to give a concrete estimation1 of how much money the poor would receive, making the “we save football” rhetoric2 look like an empty promise to the public. People rightfully felt lied to, and that’s the last thing you want to obtain in communications, be it of a sports event or a yogurt brand.

Another rhetorical figure that I personally disliked was that of the “Pyramid”, a word that appears a lot in the press release but that has also been used extensively by Florentino Pérez in his only public appearance up to this moment (at El Chiringuito). Although it served the redistribution and “solidarity” argument, I believe that this rhetorical figure graphically reinforced the distinction between of the rich 0,1% vs. the poor clubs that should not be allowed to climb up to the top — which, as we said, did nothing but making fans mad.

People, therefore, felt blatantly lied to. And that has little to do with the closed league; that’s due to the clumsy storytelling they built around it. It would be interesting to ask them if that was the message they were aiming to convey or if they just wholly miscalculated the wording of it.

Lastly, the fact that only 12 of the 15 foreseen founding members were mentioned in the announcement was simply incomprehensible. With it, they were implicitly stating that at least three of the most important clubs in Europe had declined the offer to get into the best and most remunerative competition ever made. But how could people consider it so if it didn’t have the power to gather all the best teams into it3?

No plan, no party

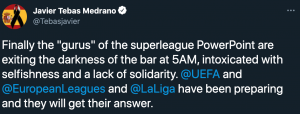

However, not everything is about what you say and how you say it. Every product, event, or campaign needs a communications plan, a timeline. The Super League didn’t have one, although it desperately needed it. The reason why has been cleverly resumed by LaLiga president Javier Tebas when the project was launched:

The Super League did not realise what its image was for the outside world: a very restricted, wealthy, and evil group of individuals meeting in secret to plot against the football everybody loves. As a consequence, issuing an announcement out of the blue without preparing the public for it was an extremely risky move. It was a leap into the unknown — which cannot be an option when there’s so much at stake.

They didn’t calculate that people were not ready for such a huge change to such a repetitive and defining feature of their lives, football. Individuals are scared of abrupt changes, especially when they affect their daily routine.

A better choice would have been to prepare the ground for the announcement gradually. Be more open to people, tell them that there was someone working on — and not plotting against — the future of football (and not only their already powerful clubs). That The Super League was not unavoidable because of the money it gave us, yet that it was desirable because of the benefits it delivered to the fans. Find someone to speak about it that people felt they could trust.

However, with that unexpected statement they willingly decided to remain the villains plotting against the fans in the “darkness of the bar at 5 A.M.”.

And when there’s no plan on how to structure your communications on the long, medium, and short term — hence, when you are not able to predict how the recipients will react to your message — you are condemned to live at the mercy of the events. That predictably happened to The Super League, which was obliged to issue yet another press release at 1:30 A.M. to state that, well, things had gotten out of hand4 but that they would have “redesigned” their proposition. That probably wouldn’t have happened with proper planning.

Is that how they wanted to be seen?

Leaving message, timing, and planning aside, let’s speak about the elephant in the room. Why on earth did they decide not to do a presentation? How is it possible that the unavoidable revolution has never been presented in a classic press conference with at least the president and the two vice-presidents? Why were we not overwhelmed by interviews of the founding members the day after?

I can find no answer to these questions. Perhaps it’s just amateurism, but that would be both too simplistic and unacceptable for a project of this magnitude.

However, there was one public appearance that explained what The Super League was. It was an interview of president Florentino Pérez — again, in the middle of the night — in a small, Spanish TV show followed by a very restricted and specific audience. Pérez sat there for almost two hours, surrounded by condescending journalists who didn’t contradicted him when he said that The Super League was there to “save football” or that “it’s not a closed league”. Outside, the world was burning and the fans were left with many questions unanswered. This interview didn’t help at all.

Furthermore, vice-president Andrea Agnelli conceded two interviews — to Italian newspapers La Repubblica and Corriere dello Sport — but the project had already been practically dismantled when they were published, making those statements obsolete. Perhaps, it would have been more productive to choose another, more immediate medium to speak in that moment — such as TV or Radio.

I believe that another flaw lies in how some clubs have announced their abandonment of the project5. Two reactions that struck me were those of AC Milan and Juventus, who highlighted that, although they had left The Super League, they remained “convinced of the soundness of the project’s sport, commercial and legal premises”6 and that “evolution” keeps being “necessary”7.

Although that’s what the club’s directors believe, it doesn’t seem a wise decision to highlight it, from a communications point of view. After the massive rejection this plan had received, the best possible strategy was to acknowledge the wrongfulness8 of the decision and to thank the fans for their opinions. These clubs have already made a hugely unpopular decision, and reiterating that they nevertheless deemed it the right choice won’t certainly make them more popular.

For the same reason, I appreciated Arsenal’s statement.

Finally, there indeed are many other errors in the overall communications strategy. For instance, the website was extremely basic, no founding commercial partners were presented (a fact that undermines the confidence of the observer), there wasn’t a social media strategy, and the brand identity seemed weak. All of these are very important aspects, but it would take too long to address all of them here.

Conclusions

The Super League fiasco will be remembered as a classic case study of how not to run a communications strategy. The lack of planning and the impossibility to convey the right message in the right way to the fans condemned it to an impressively short life.

The most surprising thing of all was how all those clubs exposed themselves to the public’s dissatisfaction without the shield of a solid communications strategy. It was like skydiving without a parachute. And it feels odd that a handful of teams that were creating a new league because of their outstanding popularity now are at risk of losing a great deal of that very popularity due to a poorly planned strategy. These clubs and their presidents, and not The Super League, are the biggest losers in this bizarre situation.

Notes

1 In truth, they said that is was “expected to be in excess of €10 billion”, yet specifying that this sum would have been given out “during the course of the initial commitment period of the Clubs”, which seems a too vague timeline. Moreover, it doesn’t specify who the recipients would be. The number of clubs/federations getting the money is crucial, since the quantity of money one gets depends on how many other people it has to share it with. In any case, the simple fact that one exactly knows the huge amount the founding clubs would get but not how much the rest would receive makes the “solidarity” rhetoric fall apart immediately.

2 Used several times by Florentino Pérez at El Chiringuito

3 Reportedly, the three missing teams were Borussia Dortmund, Bayern Munich and PSG.

4 All the English teams had already left abandoned the project and reports were already anticipating that other clubs were ready to do the same.

5 Please note that I’m not making a judgement of the clubs’ reasons. I’m suggesting the best possible communications strategy to employ here, as far as I’m concerned.

6 https://www.juventus.com/en/news/articles/statement-on-the-super-league-project

7 https://www.acmilan.com/en/news/articles/club/2021-04-21/official-statement

8 To be fair, other clubs such as Liverpool, Manchester City, or Tottenham have not apologised and/or thanked the fans.